Motion Capture via Probabilistic Inference

- 8 minsIn an effort to control my robot arm, I realize it would be good to have a way to measure the position of the arm in 3D. I could do the more typical solution of motor encoders + inverse kinematics, but this seems error prone and inaccurate especially considering just how much mechanical wiggle room exists in my system – everything is 3D printed out of PLA after all. As nothing is hugely rigid, it would be great to have a more absolute measure of position.

As such, I figured it would be fun to build a motion capture system for this purpose! The basic idea is to have a bunch of webcams, add IR filters to them, and take pictures of objects with IR LEDs on them. Then, because we are capturing from multiple points of view, the system is over constrained and we can work out the true positions.

This post talks about the first steps taken to this end and includes a preliminary discussion of the potential hardware as well as a prototype structuring of the motion capture problem as probabilistic inference! As usual, I have no real idea what I am doing so feedback is appreciated!

Hardware

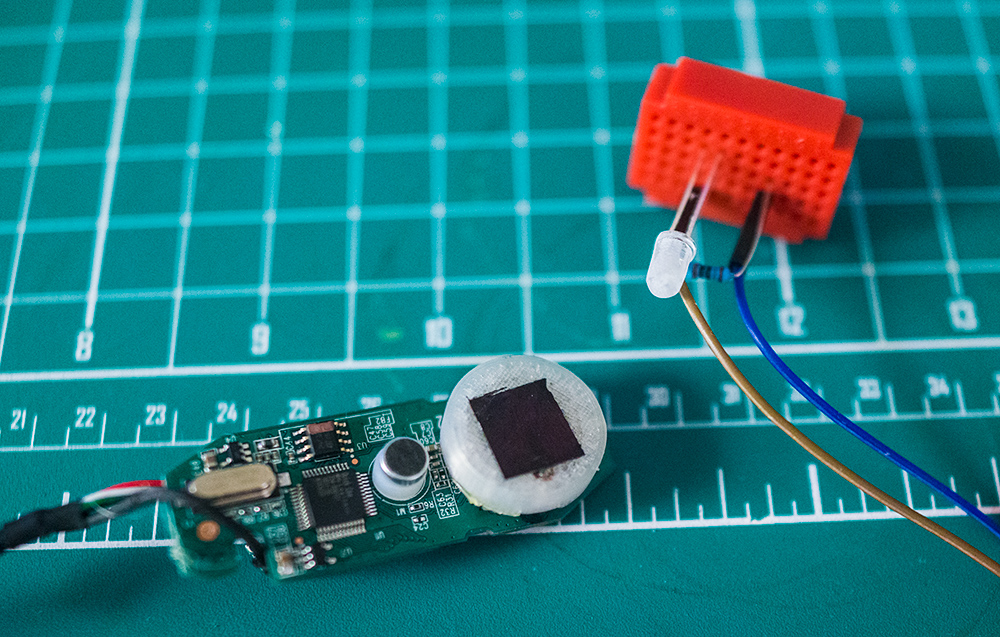

The hardware I settled on is a cheap Logitech C270 webcam for $20. I disassembled these, 3D printed little lens hoods, and attached IR filter. For markers, I took some IR LEDs and sanded down the transparent plastic to give more of a diffuse output. Below, we can see a test shot with one of these cameras. The LED is super clear and should be fairly easy to pick out via some simple computer vision.

Software: Let’s treat motion capture as probabilistic inference!

I am a Bayesian at heart, so naturally I turned to these tools when designing this system. Philosophically, this family of methods fits this project quite well – we can build low quality hardware and make up for this in software by performing inference on a model that incorporates a lot of uncertainty! For example, I don’t expect my point tracking to be perfect or any sort of syncing between cameras.

For now though, I started with something simple and entirely in a simulated world. This is great because I can specify (and thus know) the ground truth generative process. In this setup, I am assuming I have a series of 2D point readings (observed data) produced via a generative process defined by multiple virtual cameras (with unknown position and orientation) that observe multiple moving 3D points of unknown positions. The goal is to recover the camera positions and orientation as well as the positions of the points through time.

Generative model

Let’s first consider the generative model we wish to use for determining inference. Let us call the observed data, the 2D points observed from multiple cameras, \(X\) (indexed by $c$ to denote camera index and $i$ to denote point index), and the unknown variables we wish to do inference on, the camera positions and 3D point locations, \(\theta\). We can now define \(P(X|\theta)\) which is the probability that we observe the 2D position readings (\(X\)) given the underlying world (\(\theta\)).

To unpack this further, let’s first consider a single 3D point and a single 2D reading. Given a camera and a 3D point, we can project it into a 2D image. This projection is quite simple at this point and is based on a pinhole camera model. I parameterize the camera by translation, encoded as a vector with 3 components, and rotation encoded by a quaternion with 4 components. We convert these 2 values into a transformation matrix, \(T \in \mathcal{R}^{4,4}\). Given a 3D point, \(m\), we can apply this matrix, then the camera intrinsic matrix \(I\), and then finally normalize by the 3rd component to recover the 2D position, \(X_{ci}\): \(I T m = [x’, y’, s, 1]^{T}\), \(X_{ci} = [x’/s,y’/s]\). See here for more info.

Given perfect observations and cameras, this projection would map a single 3D point to a single 2D point. Because the real world is noisy, though, and to make inference easier, let’s assume we could map to one of many possible 2D values. In our case, let’s assume a Gaussian probability centered around the predicted projection. Not all points, however, will be projected onto the image. Our camera only has a finite view and can only see points in front of it. In this case, let’s just call the (unnormalized) probability of a given image a constant.

When we have multiple points, however, we need to know which 3D point belongs to which 2D point. For this, we can simply take the sum of probabilities of all possible permutations. This scales poorly O(N^2) with the number of points but should still be computable for the small number of points I expect to have. Finally, there is more than one camera, and more than one time point. To account for this, we can just take the product of these different components.

\[P(X|\theta) = \sum_{permutations of points} \prod_{cameras} \prod_{times} \prod_{points} P(X_{ci} | camera, point)\]Inference

Ideally, I will do something proper (e.g. define a prior on \(\theta\), and do MCMC or VI.) For now, though, let’s just compute a MAP estimate of \(P(X | \theta)\). Put simply, let’s just find the single most likely configuration of cameras and 3D points, \(\theta\), from which the observed 2D data, \(X\), could derive. This boils down to an optimization problem: \(\text{argmax}_{\theta} P(X |\theta)\). Coming from the machine learning community, what better way to tackle this than by writing all of this in a differentiable programming language / framework (in my case Jax), computing gradients, and doing SGD!

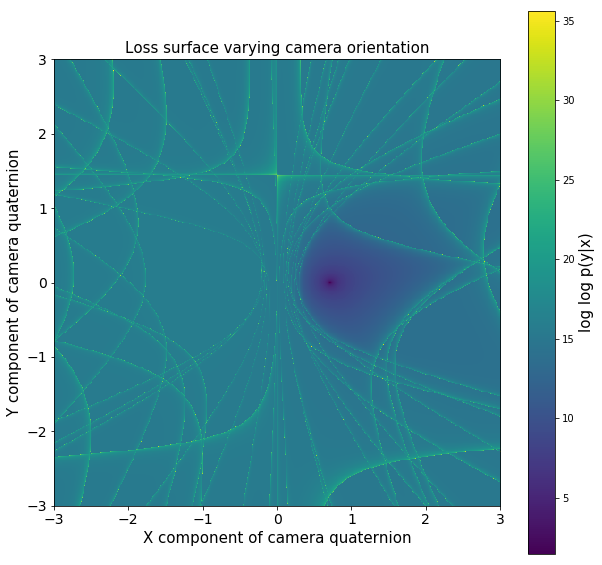

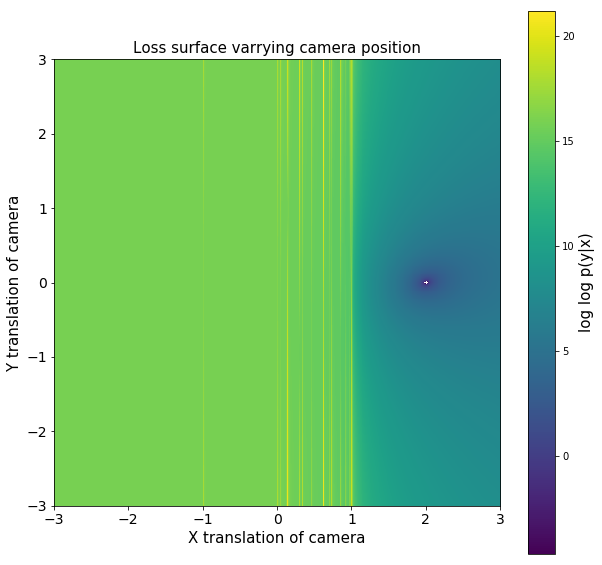

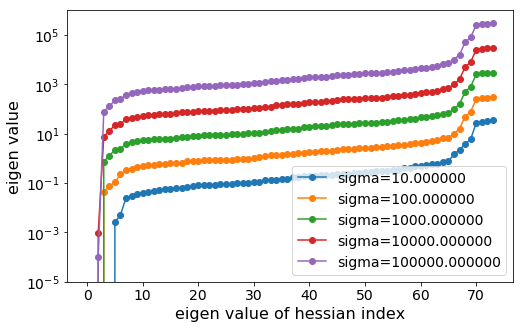

Sadly, though, the loss surface here is horrendous with local minimum and odd symmetry galore. I made some plots varying camera orientation and position to show just how wonky the loss surface is. Further, because Jax is awesome, I also computed eigenvalues of Hessians at different sigma!

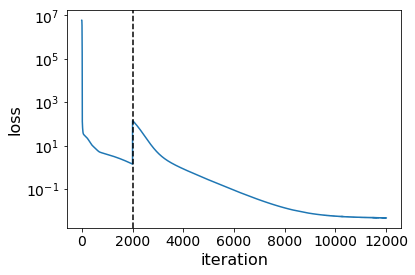

To get around this, we can do a few things. First, we can anneal the sigma, or how sharply we lose probability, if our prediction is incorrect. Because there are certain areas of the loss landscape that are high curvature, I make use of gradient clipping, a trick used in the deep learning community to train RNN. Finally, and somewhat counterintuitively for me, the more data we have, the easier the optimization process seems to be empirically.

Results

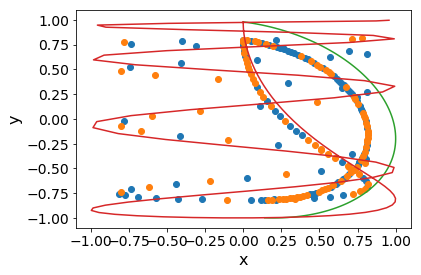

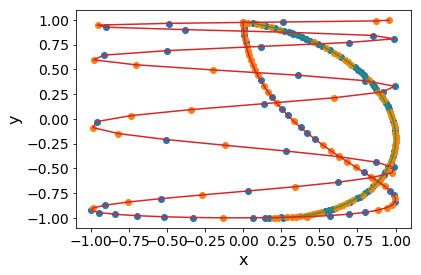

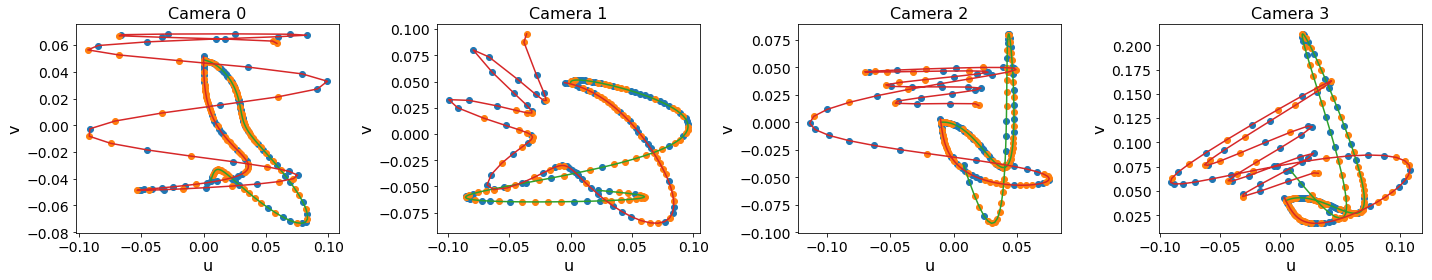

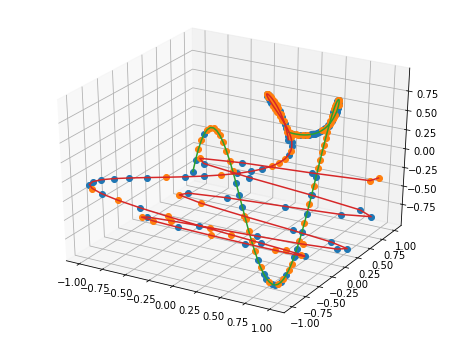

Thus far, I have tested all of this with 4 simulated cameras, at 2 points, and at 100 time points. I hardcoded the points to follow simple curves made from sin and cos. I use this ground truth data to generate the observed data, \(X\), which is a list of 2D positions – 2 for each camera. For optimization, I randomly initialize 3 of the 4 cameras, (choosing 1 camera to be fixed to try to pin down extra degrees of freedom), as well as randomly initialize all the 3D points and optimize using Nesterov momentum with gradient clipping.

While looking at the results qualitatively, I realized that there were a few unconstrained degrees of freedom in the form of rotations. This is not too hard to fix, as one can observe an object of fixed proportions and orientations and rotate. For now, though, I cheat and use the camera positions and fit a rotation matrix.

Next steps

That’s all for this quick update! Things are still progressing albeit slowly on the arm itself. Still, I did add a new axis and am working on revision 2 of the electronics. As for the motion capture system, I will be building a rig to mount cameras, collecting real data, figuring out how to go from 2D images to points, and adding in more uncertainty.

Stay tuned!