On the Difficulty of Extrapolation with NN Scaling

- 7 minsAs deep learning models get bigger and bigger, doing any form of hyperparameter tuning is becoming prohibitively expensive as each training run can cost millions. Recently, there has been a surge of interest in understanding how the performance improves as model size increases [1, 2, 3, 4]. Understanding this scaling could enable research at smaller, cheaper scales to more easily transfer to larger, more expensive, but more performant settings. By leveraging small scale experiments performed at multiple model sizes, one can find simple functions (often power-law relationships) that can predict performance on larger models before spending the compute needed to train them.

While great in theory, this has difficulties in practice. If not careful, extrapolating scaling performance can mislead, causing companies to invest millions to train a model that performs no better than considerably smaller models. In this post, we’ll walk through an example showing how this can be, as well as one reason why this could happen.

As a toy task to study these effects, let’s say our goal is to train ImageNet in a ridiculously wide MLP with 3 hidden layers. We will start small with hidden sizes of 64, 128, and 256. We use these to pick hyperparameters, in this case to find learning rate for Adam of 3e-4. We also fix the length of training to 30k weight updates with batches of 128 images.

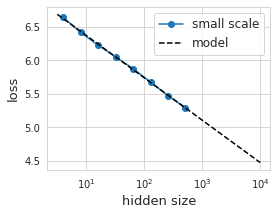

Next, we will seek to understand how our model changes with hidden size. We’ll train models ranging in size and look at how performance changes and plot the results.

The data looks surprisingly linear on this log-log plot. Great, we found our “law”! We can find the coefficients of this relation with least squares: loss(hsize) = 7.0 - 0.275 log(hsize). Empirically, this seems to hold for more than two orders of magnitude in hidden size.

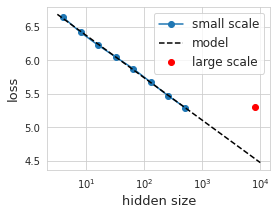

All excited about our nice looking interpolation, we thought we could extrapolate a little over one order of magnitude in hidden size to train a bigger model. However, to our dismay, we find the performance dramatically off of our predicted curve.

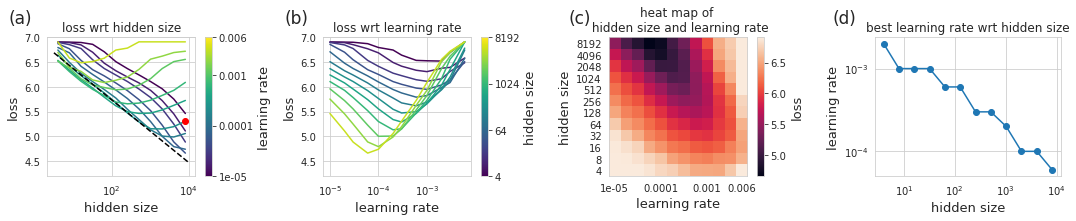

In the real world, a mess up like this could cost thousands or even millions of dollars given how big the models are these days. At the >100B parameter scale, doing any form of experimenting to figure out what is wrong with a model is near impossible. Luckily, we are working on a small scale and thus can afford the luxury of being exhaustive with our experiments – in this case we can run 12 model sizes each with 12 different learning rates (with 3 random initializations a piece) totalling 432 trials.

With this data, the story becomes quite clear and should come as no surprise. As we increase model size, the optimal learning rate shrinks. We can also see that if we simply train with a smaller learning rate, we would come close to our originally predicted performance at a given model size. We could even model the relationship between the optimal learning rate and model size then use this model to come up with yet another prediction. The plot of optimal learning rate vs hidden size (d) appears to be a power law (linear on log-log) so incorporating this wouldn’t be much trouble.

Even with this correction, how do we know we are not tricking ourselves again with some other hyperparameter which will wreak havoc in the next order of magnitude of hidden size? Learning rate seems to be important, but what about learning rate schedules? What about other optimization parameters? What about architecture decisions? What about relationships between width and depth? What about initialization? What about precision of floating point numbers (or lack thereof)? In many cases, the default, and accepted values for a variety of hyperparameters are all set at a relatively small scale – who’s to say they work with larger models?

Issues of scaling relationships seem to keep popping up as more and more folks train bigger and bigger models. Even simple things like scaling learning rates with model size as shown here is not always done (i.e. when specifying a finetuning procedure for language models). To its credit, the original scaling law paper discusses many theses issues (width/depth scaling, relationship with LR, effect of batchsize), but also acknowledges that it neglects to study many others. They also discuss relationships with compute amount and datasize but I don’t discuss or vary those here. The scaling laws they propose are designed under the assumption that the underlying model is trained with the best performing hyper parameters.

So what can we do about potentially misleading extrapolations? In an ideal world, we would have a full understanding of how every aspect of our model changes with scale and use this understanding to design larger scale models. Without this, extrapolation seems fraught and could potentially result in an expensive mistake. Reaching this point of full understanding, however, feels impossible given just how many factors are at play. Tuning every parameter at every scale is not a solution either given the computational costs.

One potential solution is to use scaling laws to predict the best case performance. As one scales up, if the performance goes off the power law relation, one should see this as a signal that something is not tuned or set up properly. I have heard this is the mindset OpenAI often uses. Put another way, when scaling doesn’t work as expected, it might mean something interesting is happening. Knowing what to do about this, or what parameters to tune to fix this performance degradation can be extremely challenging.

In my opinion, one must balance using scaling laws to extrapolate performance at larger scales, and actually evaluating performance at a larger scale. In some sense this is obvious, and a rough approximation of what is done in practice. As the study of scaling develops, I hope this balance can be made more explicit and that one can make more use of scaling relationships to enable more research at a small scale. Take this particular example, while we found that naively scaling with a fixed learning rate does not extrapolate, we did find a power law relationship between model size and learning rate which leads to models that do extrapolate within the tested model sizes. Is there some other factor that we are missing if we try to extrapolate to even larger models? Possibly. It’s hard to know without running the experiment.

Acknowledgments:

This blog is possible thanks to Google Research (my current employer) for the compute to perform these experiments. I would also like to thank Igor Mordatch, Ethan Dyer, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, Chip Huyen for reviewing early versions of this post.